Monday 11:23

March 2025

The Role of Avant-Garde Shodō in Contemporary Art

Shodō has undergone significant transformation in the 20th and 21st centuries. Artists like Shiryu Morita and Yuichi Inoue disrupted traditional calligraphic forms, integrating gestural abstraction and conceptual approaches. Their work aligns with broader avant-garde movements, such as Abstract Expressionism and Gutai, where the process of creation is as significant as the final form.

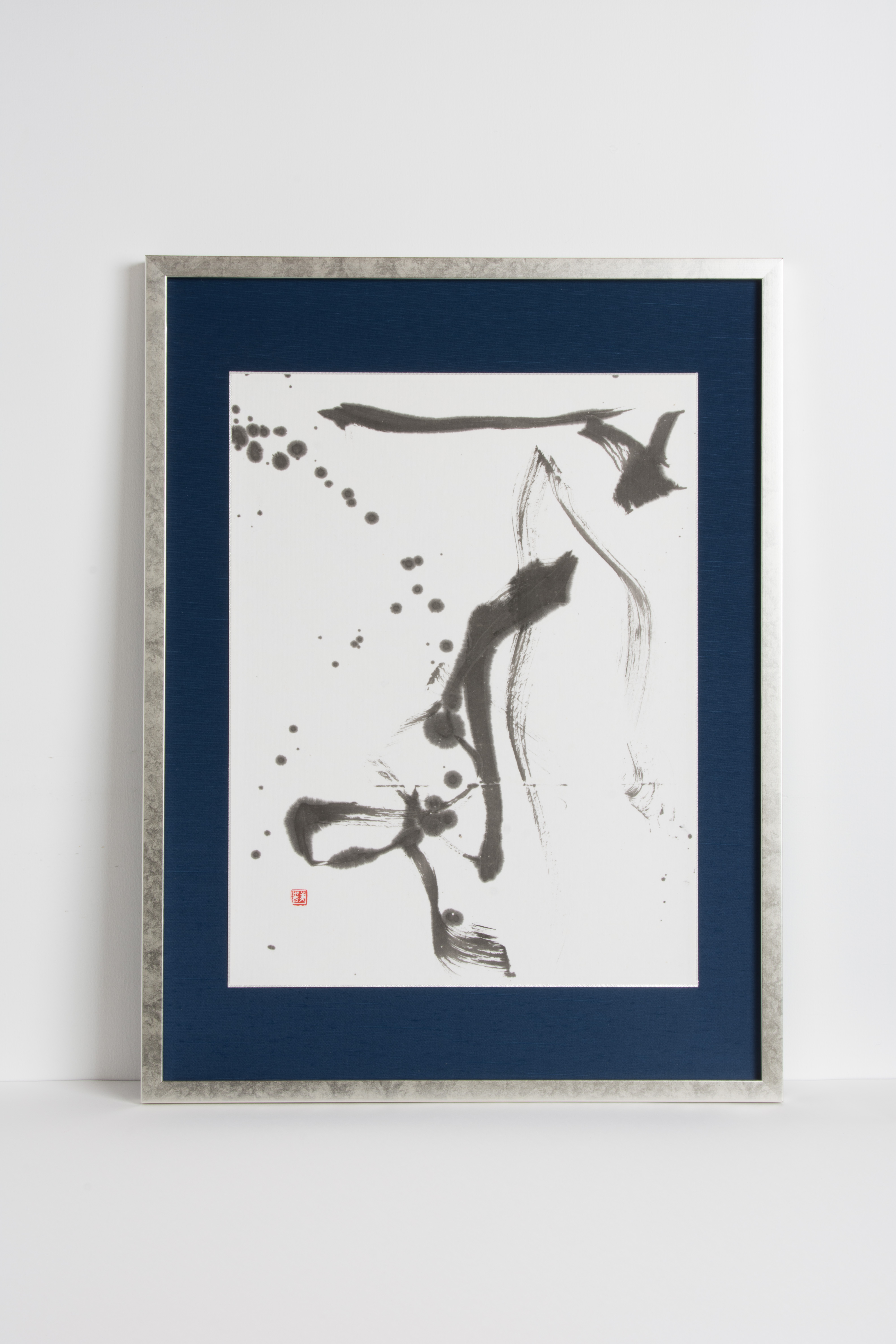

In my own practice, I approach Shodō as an evolving medium, emphasizing the performative and ephemeral nature of the brushstroke. The ink, once placed on paper, embodies an irreversible moment, much like a single film frame capturing time. Through large-scale calligraphy, I explore how brushstrokes can become traces of movement, resonating with the long-exposure techniques of experimental cinematography.

Shodō and Wave Interference: A Conceptual Approach

Wave interference, a principle in physics, describes how waves interact by amplifying or canceling each other. This concept extends beyond science into artistic and philosophical realms, offering a framework for understanding Shodō as an interplay of forces. The brush’s motion can be likened to wave propagation—each stroke generating ripples that interact with others, forming interference patterns within the composition.

In cinema, interference manifests through overlapping narratives, visual echoes, and rhythmic disruptions. Ozu’s films, for instance, utilize static long takes that allow subtle movements to interfere with the stillness, creating tension between motion and stasis. Similarly, Tarkovsky’s notion of “sculpting in time” aligns with the temporal unfolding of calligraphic practice. My Shodō works attempt to capture this essence, treating each brushstroke as a frame in a non-linear cinematic sequence.

Shodō and Cinematic Narratives

Traditional cinema relies on montage, sequencing static frames to create movement. However, Shodō operates through fluid continuity, where a single brushstroke embodies an entire sequence of gestures. This raises the question: Can Shodō be cinematic?

My research suggests that avant-garde Shodō functions as an alternative cinematic language, where brushstrokes act as temporal imprints. In contemporary experimental cinema, artists such as Stan Brakhage and Takashi Ito manipulate time and perception in ways that parallel the spontaneity of calligraphic practice. My future work aims to develop a hybrid format where Shodō directly informs film editing techniques, merging the two mediums into a unified experience.

Conclusion

This research examines how avant-garde Shodō transcends its traditional function, merging with cinematic aesthetics to explore time, movement, and interference. By integrating calligraphy into filmic structures, my practice redefines the boundaries of both mediums. Future directions include expanding this exploration through interactive installations where viewers engage with brushstrokes in real-time projection environments.

Avant-garde Shodō, much like experimental cinema, exists at the intersection of gesture and time. As digital technologies evolve, the potential for integrating traditional mediums with contemporary storytelling expands, opening new pathways for interdisciplinary artistic expression.

References

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Ozu Yasujiro. Tokyo Story. Shochiku, 1953.

Tarkovsky, Andrei. Sculpting in Time. University of Texas Press, 1986.

Morita, Shiryu. The Way of the Brush. Kodansha International, 1977.

Brakhage, Stan. Metaphors on Vision. Anthology Film Archives, 1963.

Appendix

High-resolution images of exhibited Shodō works.